|

|

|

|

**List: Samaritan Ministry the Bible ( the Bible )

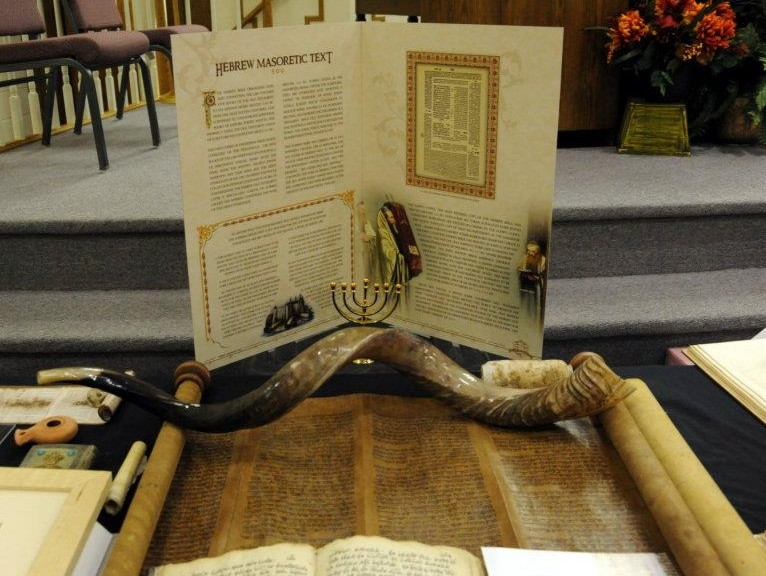

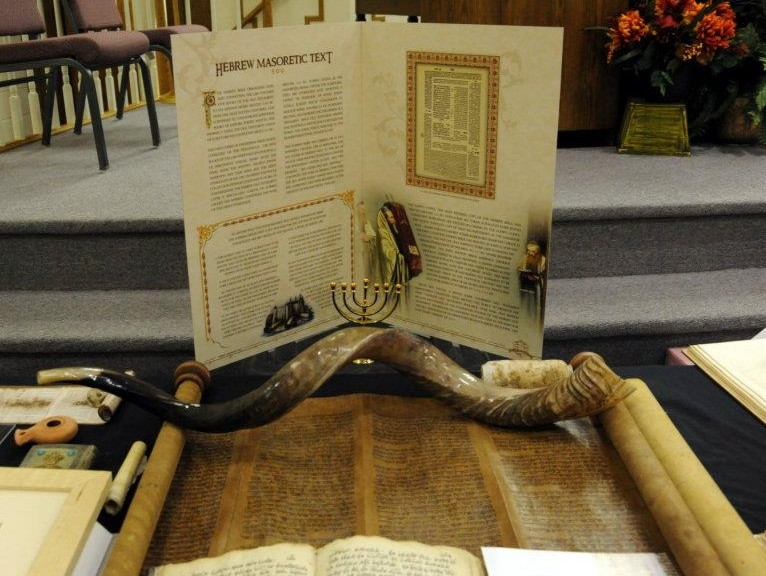

SAMARITAN. FROM WALTON’S POLYGLOT.--The Bible of Every Land. (1860, Second Edition) Samuel Bagster [Info only: Samaritan Character n.d. Exodus 20:1-17 unknown.] |

Samaritan Bible History (3)

**List: Samaritan Ministry

the Bible ( the Bible )

Samaritan...

SAMARITAN. "I.--PREDOMINANCE OF THE LANGUAGE. THE Hebrew Language (in which the Samaritan Pentateuch is written) was predominant, as we

have shown, in many countries of antiquity. It has long ceased to be the vernacular of Samaria,

the inhabitants of which region now speak Arabic; but the Sacred books and liturgy belonging to the

few remaining descendants of the ancient Samaritans are written in a dialect called the Samaritan,

which has never spread beyond the limits of Samaria itself. The Samaritans have lost all political

importance; they have dwindled down to a few families, and merely constitute a small religious

sect. They dwell on the site of Shechem, their ancient capital and chief residence, now called

Nablous or Nâbulus, a corruption of the Greek word Neapolis, the new city. Two centuries ago,

there were small Samaritan communities in Cairo, Gaza, and Damascus, as well as at Nablous. But

in 1808, there had been no Samaritans in Egypt for more than a century, and they appear now to be

confined solely to Nablous itself. Nablous, though of small size, is one of the most considerable places

in the Holy Land at the present day, and contains a population of about eight thousand; but not more

than one hundred and fifty of the number are Samaritans; and in 1838, Dr. Robinson found there were

only thirty adult males who paid taxes. They still go up three times a year to Mount Gerizim to

worship. On Friday evenings they pray in their houses; and on Saturday (their Sabbath, which they

keep with great strictness) have public prayers in their synagogue. They meet also in the synagogue

on the great festivals, and on the new moons.II.--LANGUAGES OF SAMARIA. Up to the period when the ten tribes of Israel were carried away captive into Assyria, Hebrew

was the language of Samaria. The characters employed by the ten tribes in writing Hebrew were,

however, totally different from those now in use among the Jews. The Samaritan letters, as they are

called, are closely allied to the Phœnician, and appear originally to have been employed by the whole

Jewish nation; for the characters on the Maccabean coins are very similar to the Samaritan, and thesecoins, of which the series probably commences about 150 years before Christ, were struck by Simon,

Jonathan, and other members of the Maccabean dynasty. But, unlike the other Shemitic dialects,

the Samaritans adopt no vowel-points in writing; some of the letters answer the purpose of vowels.

The mixed nature of the dialect which became predominant in Samaria on the removal of the

ten tribes, may be inferred from 2 Kings 17:24, where we are told that "the king of Assyria brought

men from Babylon, and from Cuthah, and from Ava, and from Hamath, and from Sepharvaim, and

placed them in the cities of Samaria instead of the children of Israel[;]" moreover, a Hebrew priest

was appointed as the public teacher of religion to this mixed multitude, and hence, as might have

been expected, a dialect partly Aramæan and partly Hebrew became, in process of time, the general

medium of communication. Arabic being at present the language spoken in Samaria, this dialect has

now no existence but in books; it is greatly venerated by the Samaritans, and they affirm that it is

the true and original Hebrew in which the law was given, and that the language formerly spoken by

the Jews was not Hebrew but Jewish. Implacable hatred has existed between the Jews and the

Samaritans ever since the days of Darius Codomanus, when the Samaritans separated themselves

from their Jewish brethren in faith and in ritual worship, under Manasseh, brother of the High Priest

at Jerusalem. "Say we not well[,]" said the Jews to Christ, "that thou art a Samaritan, and hast a

devil?" This feeling shows itself on every opportunity; and never more so than on the subject of

observances, the correct usage of which each party vindicates to themselves alone.III.--HISTORY OF THE HEBRÆO-SAMARITAN PENTATEUCH. The date, copyist, and origin of this transcript of the Hebrew Pentateuch are involved in inex-

tricable mystery, yet after all the discussions that have taken place on the subject, the most probable

conjecture seems to be, that when the ten tribes under Jeroboam seceded from their alliance with

Judah, they possessed this copy of the Pentateuch, which they ever afterwards carefully preserved, and

transmitted to posterity. It is written throughout in pure Hebrew, and corresponds nearly word for

word with our Hebrew Text, so that the mere acquaintance with the Samaritan characters is all that is

requisite to enable a Hebrew scholar to read this ancient document. It is rather remarkable that in

about two thousand places where the Samaritan differs from the Hebrew Text, it agrees with the Sep-

tuagint, and among the various hypotheses that have been started to account for this circumstance, it

seems most reasonable to suppose with Gesenius, that the Samaritan copy and the Septuagint version

were both made from some ancient Hebrew codex which differed in a few minor particulars from the

more modern Masoretic text. The variations of this Pentateuch do not, however, affect the force of

any doctrine, the two chief discrepancies between the Samaritan and Hebrew texts being, the prolongation

of the period between the deluge and the birth of Abraham in the Samaritan, and the substitution of

the word Gerizim for Ebal in Deut. 27. In these cases it is impossible to say whether the Jews or

the Samaritans were guilty of corrupting the original text. The Septuagint represents the contested

period as even longer by some centuries than the Samaritan, and it is followed by the Roman Catholic

Martyrology; but in the Latin Vulgate, the computation of the Hebrew text has been adopted. For

instance, the date of the Deluge is according to

the Samaritan Pentateuch, B.C. . . . 3044

The Samaritan epoch agrees best with two other important eras of the heathen world, viz:--

the Hebrew text ,, . . . . 2348

the Septuagint ,, . . . 3716

the Indian Deluge, and era of Kali-yuga B.C. . 3101

and the Chinese Empire ,, . 3082These two dates added to the Samaritan date, 3044, and divided by 3, give B.C. 3076 as the

probable date of the universal deluge. The chronology of the Samaritan has been vindicated by Dr.

Hales, but generally, where various readings exist, the authority of the Hebrew is considered paramount.

These occasional readings do not however diminish the value of the Samaritan Pentateuch as a witnessto the integrity of the Hebrew text. That the same facts and the same doctrines should be transmitted

in almost precisely the same words from generation to generation by nations, between whom the most

rooted antipathy and rivalry existed (as was notably the case between the Samaritans and the Jews),

is a strong argument in proof of the authenticity of the books ascribed to Moses; the purity of the text

handed down to us through these two separate and independent channels may likewise be argued from

the fact, that no collusion to alter passages in favour of their own prejudices is ever likely to have taken

place between two such hostile nations.

The Samaritan Pentateuch was studied by Eusebius, Jerome, and other fathers of the Church,

and in their works several citations of the various readings existing between it and the Hebrew occur.

Yet singular enough, this valuable text for about a thousand years was quite lost sight of by the

learned, and it was unknown, and its very existence almost forgotten in Europe, when Scaliger, in the

year 1559, suddenly instituted inquiries respecting it, and at his suggestion a negociation was opened

by the learned men of Europe with the remnant of the Samaritans, for the purchase of copies of this

Pentateuch. In 1616 Pietro della Valle effected the purchase of a complete copy, which was bought

by De Sancy (afterwards Bishop of St. Malo), and sent by him in 1623 to the Library of the

Oratory at Paris. In the meantime efforts were being made in England for the possession of copies,

and between the years 1620 and 1630, Archbishop Usher obtained six MSS. from the East, of which

some were complete and others not. Five of these MSS. are still preserved in England, but one copy

which the Archbishop presented to L. de Dieu seems to have been lost. At various times other copies

of the Samaritan Pentateuch have been since received in Europe, and there are in all about seventeen

which have been critically examined; of these, six are in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, and one in

the Cottonian Library in the British Museum. They are all written either on parchment or on silk

paper; there are no vowel points or accents, and the whole Pentateuch, like the Hebrew text, is divided

into sections for the service of the synagogue: but while the Samaritan has 966 of these divisions, the

Hebrew has only about 52. Some of the MSS. have a date beneath the name of the copyist, deter-

mining their age. The MS. belonging to the Oratory at Paris is supposed to have been written in the

eleventh century; our other MSS. are more recent, except one attributed to the eighth century, but its

date is very uncertain. The Samaritans themselves, however, ascribe extraordinary antiquity to their

own copies; and Fisk says that the Kohen or Priest showed him a MS. which they pretended had been

written by Abishua, great grandson of Aaron, thirteen years after the death of Moses: it was a roll, in

some respects like the synagogue rolls of the Jews, and kept in a brass case. A copy in another brass

case was affirmed to be 800 years old. Fisk observed a number of MSS. of the Pentateuch on a shelf

in the Samaritan synagogue, and he says that besides the Pentateuch they have copies of the books of

Joshua and Judges, but in separate volumes. They preserve under that name, not the same books

of the Hebrew canon, but a compilation of their own, usually known as the "Chronicon Samaritanum,"

which contains documents collected from various sources, and brought down to the time of Hadrian.

They hold no books for canonical, but the five books of Moses.

The first printed edition of the Samaritan Pentateuch was made from the Codex Oratorii (i.e. the

MS. belonging to the Oratory at Paris); it was printed by Father Morinus in the Paris Polyglot.

This text was reprinted in the London Polyglot, with corrections from three of the MSS. which for-

merly belonged to Usher; and so correct is this edition that a Samaritan priest whom Maundrell

visited at Nablous, esteemed this Samaritan text equally with a MS. of his own, which he could not

be prevailed on to part with at any price. Fisk when in Samaria saw a relict of the very copy of the

Polyglot mentioned by Maundrell. Various readings collated from the Samaritan MSS. were given

by Dr. Kennicott in his edition of the Hebrew Scriptures, as mentioned in page 28: and in 1790,

Dr. Blayney published at Oxford the Samaritan Pentateuch from the text of the London Polyglot, in

square Hebrew characters. The variations of the Samaritan text have likewise been published by

Mr. Bagster. A Grammar of the Samaritan language, with Extracts and a Vocabulary, by Mr. G. F.

Nicholls, was published by Messrs. Bagster, in 1858.IV.--HISTORY OF THE SAMARITAN VERSION. Three versions have been made of the Samaritan Pentateuch, two of which only are now extant.

The first version was made from the Hebræo-Samaritan text into the Samaritan dialect, but the date

and author are unknown: by some writers it is ascribed to the period when a Hebrew priest was sent

by Esarhaddon to instruct the mixed multitude of Samaria in the service of God; while others affirm

that it was executed in the first or second century of the Christian era. This version is in the highest

degree exact and literal; it is, in fact, a complete counterpart of the parent text. In some instances,

however, its resemblance to the Chaldee Paraphrase of Onkelos is very striking, and there are no means

of accounting for this singular agreement, unless we adopt the supposition that it fell into the hands

of Onkelos, and that it was interpolated by him. It has been printed in the Paris and London Poly-

glots; and in 1682, Cellarius published extracts from it with Latin annotations and a translation. Copious

extracts are also given in Uhlemann’s Institutiones Linguæ Samaritanæ.

When the Samaritan dialect fell into disuse, and the language of the Arabian conquerors became

the vernacular of the country, the Samaritans had at first recourse to the Arabic version of Saadias

Gaon, at that period in general use among the Jews. A translation into the Arabic language as spoken

in Samaria, and written in Samaritan characters, was afterwards prepared by Abu Said. It is not

known with certainty in what year this translation was made; Saadias Gaon died A.D. 942, and it

must have been made subsequently to that period, as Abu Said made great use of that Jewish rabbi’s

labours. This version is remarkably close and literal, and follows the Samaritan even in those readings

in which it differs from the Hebrew text. Several MSS. of this version still exist in libraries, but the

whole has never been printed. A third version of the Samaritan Pentateuch was made into Greek,

but this work, though quoted by the fathers, is no longer extant. The Samaritan and Arabic versions,

from their noted fidelity, are of much value in correcting the text of the Samaritan Pentateuch, and

in fact form almost the only sources for its emendation."--The Bible of Every Land. (1860, Second Edition) Samuel Bagster [Info only]SAMARITAN. FROM WALTON’S POLYGLOT.--The Bible of Every Land. (1860, Second Edition) Samuel Bagster [Info only: Samaritan Character n.d. Exodus 20:1-17 unknown.]

[Christian Helps Ministry (USA)] [Christian Home Bible Course]