|

|

|

|

**List: Aramaic Ministry Bible ( Ktaba

)

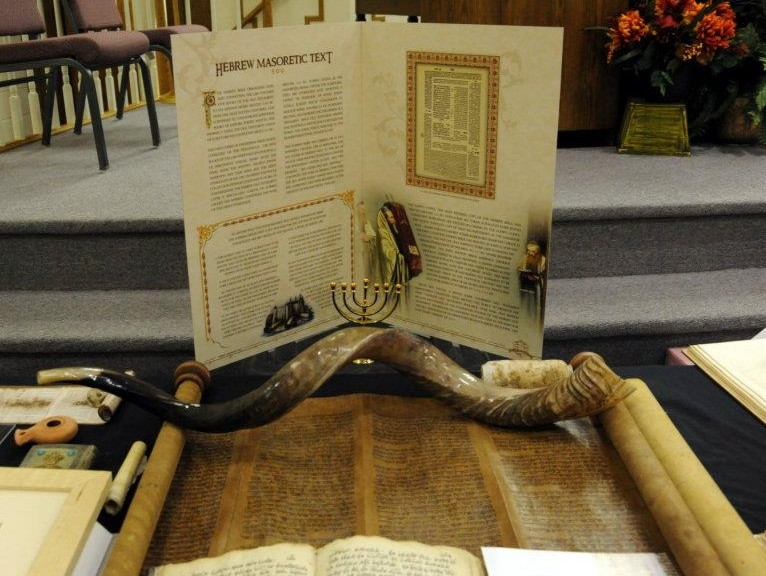

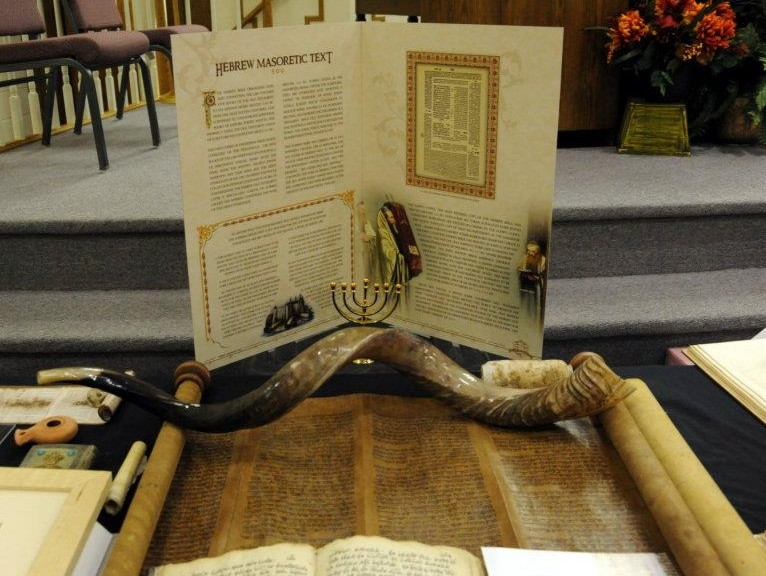

CHALDEE. THE TARGUM OF ONKELOS, FROM WALTON’S POLYGLOT.--The

Bible of Every Land. (1860, Second Edition) Samuel Bagster [Info

only: |

Aramaic Bible History (3)

**List: Aramaic Ministry

Bible ( Ktaba )

Aramaic...

CHALDEE. "THE Aramæan or Syrian language appears from the earliest times to have been divided into two grand

branches, namely, the West Aramæan or Syriac, which was the dialect spoken towards the West, in

Syria and Mesopotamia; and the East Aramæan, generally denominated the Chaldee, which was spoken

towards the East, in Babylonia, Assyria, and Chaldæa. But this division of the Aramæan language

into two branches is rather geographical than philological, for with the exception perhaps of a few

words and forms peculiar to each dialect and some variations in the vowels, no very great difference

exists either in grammatical structure or lexicography, between Syriac and Chaldee. In general, how-

ever, the vowels are pronounced broader in Syriac than in Chaldee; in Syriac the sound O taking the

place of that of A in Chaldee. Michaelis, indeed, has remarked, that the Chaldee of Daniel becomes

Syriac if read by a German or Polish Jew. The chief point of distinction between the two dialects is,

that Syriac is written in characters peculiar to itself, whereas the square characters, which are also

appropriated to Hebrew, are employed in writing Chaldee. Down to the time of Abraham, Chaldee

is supposed to have been almost, if not quite identical with Hebrew, and to have acquired subsequently

the peculiarities of a distinct dialect. The dialect spoken in Chaldea was the original language of

the Abrahamidæ, for Abraham was called from "Ur of the Chaldees." And since "Ur" is to the

north of Mesopotamia, and the "Chaldees or Chasdim" came originally from that part of the country,

we may infer that the vernacular language of Abraham, whatever that may have been, was the lan-

guage originally spoken between the Euphrates and the Tigris (Gen. 11:31). Isaac and his family

spoke Hebrew, which was the language of Canaan, the land in which they sojourned, and Hebrew con-

tinued to be the language of their descendants till the time of the Babylonish captivity.

During the seventy years passed at Babylon the dialect of the captives seems to have merged into,

or to have become greatly adulterated with, that of their conquerors, and the great similarity in genius

and structure between the two dialects naturally accelerated the effects of political causes in producing

this admixture. On the return of the Jews to Jerusalem, it was the custom of the priests to read the

law of Moses publicly to the people, and afterwards to give an exposition (see Neh. 8:8, etc.). It is

the opinion of many eminent scholars that the law was read as it stood in the original Hebrew, but

explained in Chaldee, the only dialect then generally intelligible among the Jewish people. Howeverthis may have been, it is certain that at least as early as the Christian era, written expositions of

--The Bible of Every Land. (1860, Second Edition) Samuel Bagster [Info only]

Scripture in the Chaldee dialect were in circulation among the Jews; and the name of Targums, from

a quadriliteral root signifying an explanation or version, was given to these Chaldee compositions.

The most ancient Targum now extant is that written by Onkelos, a disciple of Hillel, who died

60 B.C. This Hillel is by some supposed to have been the grandfather of Gamaliel, Paul’s instructor.

In purity of style Onkelos equals the Chaldaic sections of Ezra and Daniel, and his fidelity to the

Hebrew text, which he generally follows almost word for word, is so great, that he deserves to be

looked upon as a translator, rather than as a paraphrast. No writings of his are extant except his

Targum of the books of Moses, which has been printed with a Latin translation in the first volume of

the London Polyglot; it is esteemed of much service in biblical criticism from the fact of its being

supported, in passages where it differs from the Masoretic text, by other ancient versions.

Besides the Targum of Onkelos, seven other expositions of Scripture in the same dialect, though

greatly inferior in merit, are now known to be in existence. The Targum of Jonathan Ben Uzziel

upon the greater and lesser Prophets is believed by some authors to have been written about 30 B.C.:

though others assign it a later date; it abounds in allegories, and the style is diffuse and less pure than

that of Onkelos. It conforms generally to the Masoretic text, but differs from it in some important

passages. A Targum written by another Jonathan (hence called the Pseudo Jonathan) made its appear-

ance at some period subsequent to the seventh century: the style is barbarous, and intermixed with

Persian, Greek, and Latin words; it is confined to the Pentateuch, and generally follows the rabbinical

interpretations, hence it is of no use in criticism. The Jerusalem Targum is also upon the Pentateuch;

but it is in a very mutilated state, whole verses being wanting and others transposed: it repeats the fables

contained in the Pseudo Jonathan, and is written in the same impure style; by many, indeed, it is

considered merely as the fragments of an ancient recension of the Pseudo Jonathan. The Targum of

Joseph the Blind on the Hagiographa is also written in very corrupt Chaldee, and adulterated with

words from other languages. The remaining Targums (on Esther and Canticles) are too puerile and

too paraphrastic to be entitled to notice here. The first seven Targums are all printed in the London

Polyglot; the eighth (on the Chronicles) was not known at the time of the publication of that work;

it was discovered in the Library at Cambridge, and published at Amsterdam in 1715. Beck had pre-

viously published large fragments from an Erfurt MS., in 1680-81, at Augsburg. The great utility

of the earlier Targums (for the later Targums are of little or no use), consists in their vindicating the

genuineness of the Hebrew text, by proving that it was the same at the period the Targums were made,

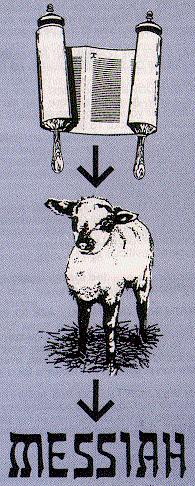

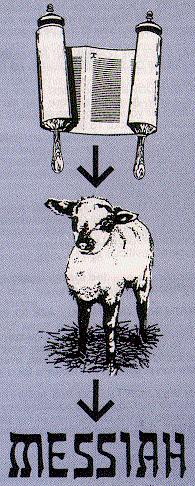

as it exists among us at the present day. The earlier Targums are also of importance in showing that

the prophecies relating to the Messiah were understood by Jews in ancient times to bear the same

interpretation that is now put upon them by Christians. And it must be added, that, in developing the

customs and habits of the Jews, in exhibiting the aspect in which they viewed contested passages of

Scripture, and in denoting the mode in which they made use of idioms, phrases, and peculiar forms

of speech, considerable light is derived from the Targums in the study both of the Old and of the

New Testament."CHALDEE. THE TARGUM OF ONKELOS, FROM WALTON’S POLYGLOT.--The Bible of Every Land. (1860, Second Edition) Samuel Bagster [Info only:

Hebrew Character n.d. Exodus 20:1-17 unknown.]

[Christian Helps Ministry (USA)] [Christian Home Bible Course]