|

|

|

|

**List: German Ministry the Bible ( die Bibel )

|

Deutsch / German Bible History (2)

**List: German Ministry

the Bible ( die Bibel )

German...

"Few vernacular Bibles in the major tongues of Europe are to

the same degree a "one-man Bible" as the German Bible of Mar-

tin Luther. To add to this, there is the enormous influence this

Luther version had on the translators into other languages who

followed him. The place of leadership he held in the Reforma-

tion of the [traditional] Church doubtless contributed to this influence, but

it does not account for all of it. For the men and women of the

sixteenth century read Luther’s rendering of the sacred writers and

pronounced it "good."

A mere recital of the dates, places, printers, formats and types

of a Scripture edition can never tell the heart of the story of its

making. Least of all could this be so in the story of Luther’s

earliest German Scriptures. A mighty personality was wrought

into them. The man to whom the [religious] world was so real and

near, and to whom the struggle between good and evil, truth and

falsehood so actual, that it could credibly be told of him that he

threw his inkpot at the devil when hindered in his greatest task

with pen and ink,--such a man can scarcely be judged by cold

standards of literary criticism when his output is compared with

that of other men.

Even a foreigner with but small knowledge of the German

tongue can sense the homely forcefulness of Luther’s Bible. To

the men of his own race it appealed with a power that must havebeen comparable to the effect on the ancient churches when they

first read Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians or the Gospel of John.

The German scholar Fritzsche gives this verdict on Luther as a

translator: "As far as the German language is concerned, Luther

was just the man to achieve remarkable results. Himself a Ger-

man through and through, sprung from the people and planted

in their midst, he mastered, as no one else of his time, the very

stuff of the language as it then lay at hand, and could therefore

give free play to his own creative genius." The Historical Cata-

logue of Printed Bibles, which gives (p. 492) this quotation, pic-

tures as follows some of those "remarkable results:" "As Luther’s

Bible at once became the most widely read book in Germany, it

naturally exerted a commanding influence on the development of

the German language. At first the editions which appeared in

South Germany . . . required numerous dialectic changes or expla-

nations of words. But a hundred years later Luther’s High Ger-

man was everywhere dominant in schools as well as churches."

It was no vacuum into which this version was projected. To

say nothing of the manuscripts of Scripture in German dialects,

which had circulated for centuries, there were at least eighteen

editions of the whole Bible, besides numerous Psalters and other

Portions, that had been printed before Luther issued his New

Testament in 1522. Since printing was first achieved by a Ger-man on German soil, it is no surprise to see that the earliest Bible

--1000 Tongues, 1939 [Info only: ?]

printed in any modern language was the German Bible of 1466,

at Strassburg, editor unknown. But [some, not] all these texts, of manuscripts

and of printed books alike, were rendered from the Latin Vulgate.

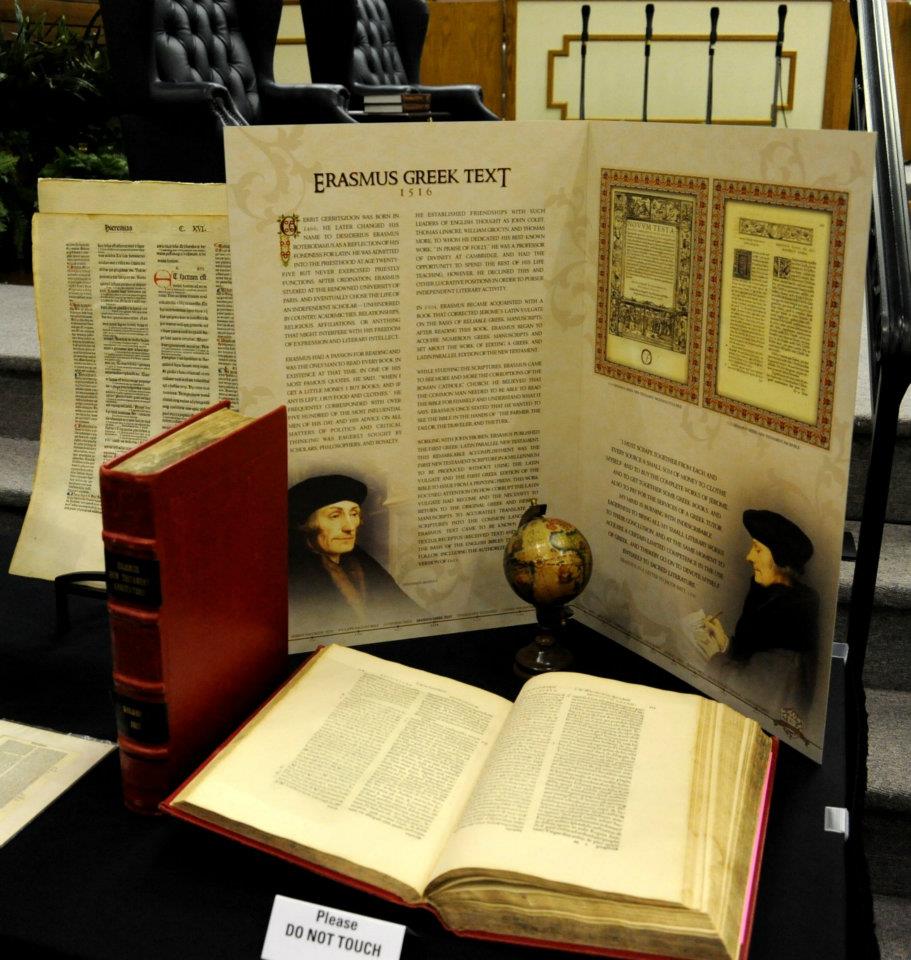

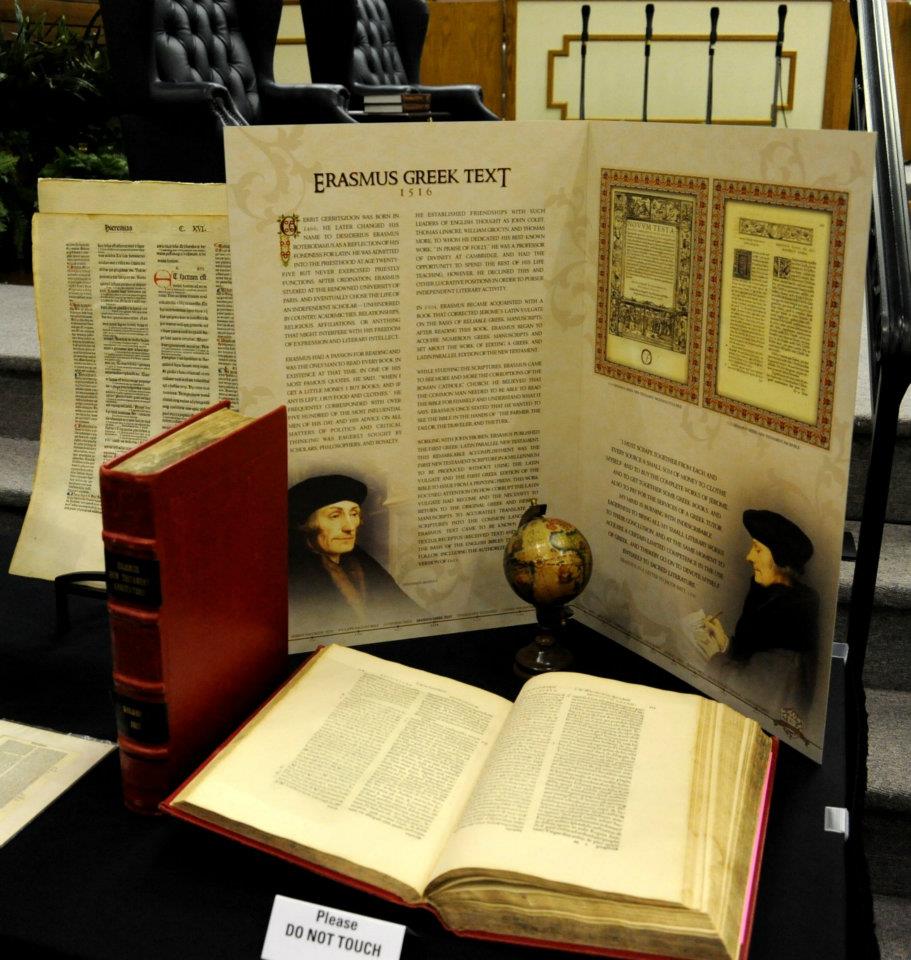

Luther’s New Testament was the first to make use of the Greek

text of Erasmus: he used the second edition of it, which had been

issued only three years before his own book was finished and only

a year before he had begun it.

Three folio volumes appeared two years later, in 1524, as the

earliest instalments of the Luther Old Testament. These con-

tained only the books from Genesis to the Song of Solomon. It

was eight more years before the rest of the canonical books (the

Prophets) were issued. And in 1534--only one year before Miles

Coverdale’s first English Bible appeared--the first complete Bible

of Marin Luther was printed at Wittemberg. So popular, how-

ever, were the parts separately issued, that there are many Bibles

listed as "combined Bibles," because they used Luther’s version

as far as it was available and drew the rest from other sources or

rendered anew for themselves. Such for example was the Swiss

Bible of 1529, in six volumes, published by the Reformed Church

of the city of Zurich, and reissued in a single volume two years

later, with some revisions and with a preface by the celebrated

Reformer Zwingli.""Painstaking study of these early Bibles of Central Europe,

whose appearance coincided with the progress of the Reforma-

tion, has revealed much of interest in the interlocking literary and

doctrinal relationships between the translators, the editors, the

printers and the artists who united to produce them. None of

them can be safely studied or judged as a separate undertaking.

And the center of such study lies in the career of Martin Luther,

not only as a Biblical scholar but also as a leader of European

thought in the first half of the 16th century."--1000 Tongues, 1939 [Info only:

No endorsement of M. Luther's soteriology.]"Most German Bibles printed in the centuries since have been

revisions of the Luther text. Some have been official, some pri-

vate. Some have been issued by State Churches, with "approba-

tion" such as that enjoyed by the first edition from the Elector of

Saxony. Many, especially in recent years, have been planned and

circulated by Bible Societies. In very recent times numerous

German Scriptures, chiefly New Testaments, have made their

appearance, giving the German reader as many independent ver-

sions, based on modern texts of the Greek New Testament, ... with

or without comparison of the original text. All these afford a wide

choice to the German reader, according to his preference for free-

dom or literalism and the measure of his loyality to the now tradi-

tional phrases of Luther’s "classical" German."--1000 Tongues, 1939 [Info only:

Many German bibles after 1912 are Critical Text.]

[Cristian Helps Ministry (USA)] [Christian Home Bible Course]