|

**List: Latin Ministry

the Bible ( the Bible )

Latin...

|

"III.--VERSIONS OF THE SCRIPTURES IN THIS LANGUAGE.

We possess no direct evidence as to the time when the

Scriptures were first translated into Latin.

There is no reason to suppose that a Latin translation would be peculiarly

wanted by the large body of

Christians residing at Rome in the

earliest ages, for Greek was well understood by both the educated

and uneducated. This language spread among even the lower classes,

from the great influx of

strangers into the capital of the civilised earth, with whom Greek was the

general language of com-

munication, as well as from the vast number of slaves in Rome brought from

countries where Greek

had obtained some footing: besides this, the near proximity of Rome to the

cities of Magna Græcia, to

which the franchises of the jus Latinum had been extended, must have

had no small influence. And

indeed the fact of St. Paul having written in Greek to the

church at Rome, may be taken

as at least an

indication that Latin was not absolutely required by the Christians in

that city.

A Latin version had, however, been made some time before the end

of the second century. Such

a version was used by Tertullian, who criticised it, and condemned some of its

renderings. Many have

supposed that there existed originally numerous independent Latin

translations; and in proof of this

they have turned to passages in Jerome and Augustine,

which speak of the multiplicity of translations,

and they have also pointed out how differently the same texts are read by

different Latin Fathers. The

statements, however, of Jerome and Augustine may be

better understood as relating to what versions

had become through repeated alterations; and the variety in citations appears

to have arisen

partly from the use of such altered versions, and partly from writers having

translated passages for

themselves.

Lachmann especially has given good

reasons for supposing that at first there existed but one

version in Latin, and that it was made in the north of Africa, in that Roman

province of which

Carthage was the metropolis. Like most of the other ancient versions,

we know not from whose hand

it sprung; and it does not seem as if much authority was attached

to it, otherwise private individuals

would hardly have felt themselves at liberty to alter it almost at

pleasure.

As this version was made from the Greek, it was in the

Old Testament based on the

LXX., and

not on the original Hebrew. Hence it has resulted, that when a version

of the Old Testament into

Latin had been made from the Hebrew, the

older version fell after a time into such oblivion, that only

fragments of it have come down to us.

In the latter part of the fourth century, the process of

continually altering and correcting the

Latin copies occasioned great confusion: this was remarked by Jerome, Augustine, and others. The

latter of these Fathers speaks of the multiplicity of the versions then

current, and, amongst them all,

commends one which he calls the Itala. This term has occasioned

much discussion, and much mis-

apprehension. Some have thought the word Itala to be an error;

while others have strangely applied

the name of Itala or Italic to all the Latin versions extant

prior to the time of Jerome. It is evident,

however, that Augustine meant some one

version, and that it was one which had been revised, and that

the name indicates its connection with the province of Upper Italy (Italic in

contrast to Roman), of

which Milan (Mediolanum) was the capital. It is well known how closely

Augustine was connected

with Milan; it might, we believe, be shown, that in his day pains were taken

to revise the Latin

copies in that very district. One thing at least is certain, that

however common it may be to call the

ancient Latin versions indiscriminately "the Old

Italic," the name ought to be rejected, as having

originated in misconception, and as perpetuating a confusing error. [CHM note: Italic is

correct usage.]

Before we speak of the labours of

Jerome for the revision and retranslation of the Latin

text, we

have to mention what editions have been published of the older

translations.

In 1588, Flaminio Nobili published at

Rome a work which professed to be the ancient Latin

version of the Old Testament, made from the Greek: it was, however, always

considered doubtful from

what sources Nobili had taken the passages, so as to give the Old Testament

complete; and now it is

certain that he really in general did nothing but translate into Latin

the Sixtine text of the LXX.

Sabatier, one of the distinguished French

Benedictines, published at Rheims, in 1743-49, a very

large collection of fragments of the ancient versions: he drew them from MSS.

and citations: the

modern Vulgate is placed by the side of the more ancient text, and the

various citations of Latin

Fathers are given very elaborately in the notes. Besides the

collection of Old Testament fragments

given by Sabatier, some passages of Jeremiah,

Ezekiel, Daniel, and Hosea, were found by Dr. Feder, in

a Würzburg Codex Rescriptus; and they were published by Dr. Münter

in 1821. Cardinal Mai has

also given, in his Spicilegium Romanum, vol. ix. 1843, some fragments

of such a version.

The term Ante-Hieronymian is often used as a general

expression for denoting all the versions or

revisions made before the labours of Jerome.

Of these we possess not a few of the Gospels, and some

of other parts of the New Testament. Martianay published, in 1695, an

old text of St. Matthew's

Gospel and of the Epistle of St. James. In 1749 (as has been

mentioned), Sabatier published all he

could collect of the New Testament. In the same year, Bianchini

published at Rome his Evangeliarum

Quadruplex, containing

the Latin texts of the Gospels, as found in the Codices Vercellensis,

Veronensis,

Brixianus, and Corbeiensis. Subjoined there

were some Latin texts of parts of Jerome's version. The

principal of these was the Codex Forojuliensis. In 1828, Cardinal Mai gave, in his "Collectio

Vaticana," vol. iii., an Ante-Hieronymian version of St. Matthew's

Gospel, from a MS. which in the

other Gospels followed Jerome's version. We have, in the last

place, to mention the "Evangelium

Palatinum," a purple MS. at Vienna, of which Tischendorf published a magnificent edition in 1847.

Besides these Latin texts, there are also others of which we

cannot speak with entire certainty, as

they accompany a Greek text in the same MS.: they may probably,

therefore, be versions which never

had a separate circulation. Hearne published in 1715, at Oxford, the

Greco-Latin Codex Laudianus

of the book of Acts; in 1793, Kipling edited the Codex

Bezæ of the Gospels and Acts; and, in 1791,

Matthæi published the Codex Boernerianus of St. Paul's Epistles, which

has an interlineary Latin

version: a similar copy of the Four Gospels, Codex Sangallensis, was

published in 1836, by Rettig."--The Bible of Every Land. (1860, Second

Edition) Samuel Bagster [Info only:

See Old Latin Version, pp. 102-109, Jack A.

Moorman.]

|

LATIN. ANTE-HIERONYMIAN VERSION {Old Latin}.--1860 S.

Bagster [Info only: n.d. Exodus 15:1-13 unknown; used Domino for

Jehovah.]

LATIN. ANTE-HIERONYMIAN VERSION {Old Latin}.--1860 S.

Bagster [Info only: n.d. John 1:1-14 correct (unigeniti = "only

begotten").]

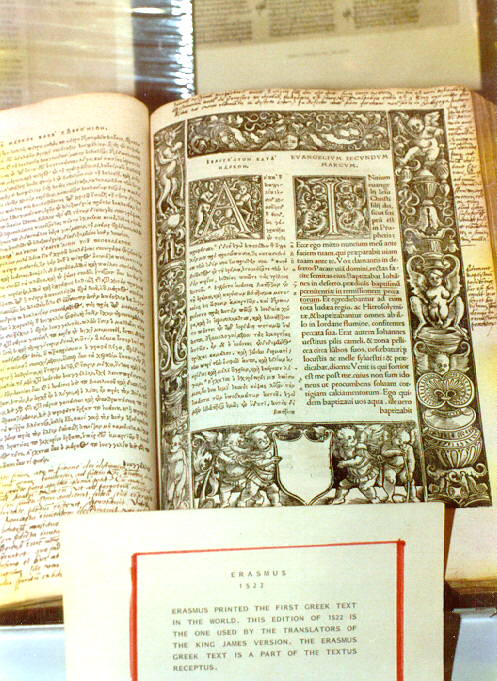

"Several important Latin versions,

comprising only the New Testament, have been executed from

the Greek text. The first of these, in point of

time, is that of Erasmus,

which was published at Basle,

in 1516, with the Greek text.

It contained a dedicatory epistle to Pope Leo X., and was highly

commended by that pontiff; yet it was regarded with great

hostility by the members of the Roman

Catholic Church, and, on its first appearance, excited much

opposition. Erasmus drew his version not

only from printed copies of the Greek Testament, but also from four Greek

MSS., and in the rendering

of several passages, he consulted the ecclesiastical writers. He does

not, however, make any notable

departures from the Vulgate, and wherever he felt compelled

to deviate in any degree from that version,

he assigned his reasons for so doing in the notes which

accompany his work. The version of

Beza is

bolder and more faithful than that of Erasmus, and does not betray the same timid adherence to the

Vulgate. It has been greatly condemned in

consequence by Roman

Catholics, but it is generally

preferred by Protestants to all other Latin versions. Its style is

clear and simple, but its chief excellence

consists in its accurate and exact interpretation of the sacred

original.

Thalemann published another Latin version of the Gospels and

Acts in 1781, and Jaspis completed

the work by translating and publishing the Epistles in 1793-1797 at Leipsic.

In 1790, a version of

the entire New Testament was published at Leipsic by Reichard. A

translation, professedly executed

from the Alexandrine text, was published by Sebastiani, London, 1817; but it

is well known that this

editor merely followed the common Greek text. The versions of Schott,

Naebe, and Goeschen, were

printed as accompaniments to critical editions of the New Testament: they all

appeared at Leipsic;

that of Schott in 1805, that of Naebe in 1831, and that of Goeschen in

1832."--The Bible of Every Land. (1860, Second Edition) Samuel

Bagster [Info only]

|

- "The version of

Castalio or Chatillon was printed at Basle in 1551, with a

dedication to

Edward VI., king of England. It was reprinted at Basle in 1573, and at

Leipsic in

1738. The design of Castalio was to produce a Latin translation of

both Testaments

in the pure classical language of the ancient Latin writers."--1860

S. Bagster [Info only: Protestant.]

|

LATIN. CASTALIO'S VERSION.--1860 S. Bagster [Info

only: n.d. Exodus 15:1-13 unknown; used Iouæ & Ioua.]

LATIN. CASTALIO'S VERSION.--1860 S. Bagster [Info

only: n.d. John 1:14 correct (unigenæ = "only begotten").]

- "Schmidt's version

of the Old and New Testaments was executed with great exactness from the

original texts, and printed at Strasburg in 1696. Several more recent

editions have

been issued."--1860 S. Bagster [Info only:

Protestant.]

|

LATIN. SCHMIDT'S VERSION.--The Bible of Every Land. (1860, Second

Edition) Samuel Bagster [Info only: n.d. Exodus 15:1-13 unknown;

used JEHOVÆ & JEHOVAH.]

LATIN. SCHMIDT'S VERSION.--1860 S. Bagster [Info

only: n.d. John 1:14 correct (unigeniti = "only begotten").]

- "The version of

Dathe, professor of Oriental literature at Leipsic, appeared in 1773-

1789, and

is considered a faithful and elegant translation of the Hebrew text."-

-1860 S. Bagster [Info only: Protestant.]

|

LATIN. DATHE'S VERSION.--1860 S. Bagster [Info only:

n.d. Exodus 15:1-13 unknown; used Jovæ & Jova.]

LATIN. SEBASTIAN'S VERSION.--1860 S. Bagster [Info

only: ~1817 John 1:14 correct (unigeniti = "only begotten").]

- "The version of the

Pentateuch by Schott and Winzer was translated from the Hebrew,

and

published at Leipsic in 1816."--1860 S. Bagster [Info

only: Protestant.]

|

LATIN. SCHOTT’S VERSION.--1860 S. Bagster [Info

only: ~1805 John 1:1-14 correct (unigeniti = "only begotten").]

LATIN. GOESCHEN’S VERSION.--1860 S. Bagster

[Info only: ~1832 John 1:1-14 correct (unigeniti = "only begotten").]

|